"A Highly Collectible Rock Plays a Key Role in the Oscar-Nominated Film ‘Parasite.’ Here’s the Actual Meaning Behind It"

Suseok have been collected for hundreds of years in Korea.

Can a rock change your luck? The Oscar-nominated Korean thriller, Parasite, argues that it might. But not just any stone slab will do, of course; it has to be a suseok, a type of natural rock collected across Korea, China, and Japan for centuries.

When the film’s director, Bong Joon-ho, was a kid, he used to hike with his dad and hunt for these collectible stones. That isn’t a popular Korean weekend pastime anymore; many youngsters don’t even know what suseok are. Still, Bong incorporated one such rock into Parasite, which is competing for Best Picture (and five other categories) at this week’s gilded awards ceremony.

It was a “deliberately strange choice” to embed suseok in the film, Bong admitted to The Hollywood Reporter. The rock appears within the first 10 minutes of the tragicomedy, when wealthy twenty-something Min-hyuk delivers a suseok to the grimy basement apartment of his down-and-out friend, Ki-woo, and his family, the Kims. “This stone here is said to bring material wealth to families,” Min-hyuk explains of the gift, taken from his grandfather’s personal collection. Meant to give the destitute family a leg up out of poverty, the suseok reappears throughout Parasite during important plot points.

(Warning: major spoilers below!)

What qualities do these “scholar’s rocks” have?

Suseok are shaped naturally, by elements like wind and water, and can range in size from monumental boulders used in landscaping to smaller stones that were historically kept on scholars’ writing tables (giving them the nickname, “scholar’s rocks”).

Connoisseurs who collect suseok—either by going out into nature and finding them, or buying them through a dealer—know to look for certain qualities. “Collectible rocks should be hard in density,” explains Kyunghee Pyun, an art history professor at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology specializing in the history of collecting. Those in the know “don’t collect loose, granuled rock, or get a rock that might break.”

Surfaces with a bit of a pattern or a wave, like the striated suseok in Parasite, are also more desirable, Pyun notes. “Round, three-dimensional is better than sort of a thin slab of stone,” she adds. “Almost like a porcelain type of quality, it should be seen from all directions.”

What role do suseok play in Parasite?

Min-hyuk presents the suseok, fitted with a custom-made base, in an impressive wooden box. The striking collectible is clearly out of place in the Kims’ dingy, subterranean apartment, where socks hang from a ceiling rack and stink bugs amble across the kitchen table.

“This is so metaphorical!” Ki-woo says, holding the rock for the first time. The suseok seems to be charmed; things quickly start to improve for the family. Though the family is all unemployed, without phone service, WiFi, or enough to eat at the beginning of Parasite, they gradually all land service jobs working for the wealthy Park family—helping clean house, drive, and tutor the children.

But the suseok resurfaces when the Kims’ luck starts to fail. When their basement apartment floods during a dramatic storm, one of the few things Ki-woo salvages from his home is the rock—which magically (and gravity-defyingly) floats up to him through septic water. He hugs the rock tightly later that night while sleeping in an emergency shelter, clinging to hope that the suseok will rescue him from poverty.

The rock next pops up when Ki-woo brings it to the Parks’ mansion, intending to kill an unfortunate couple, living in a secret subterranean bunker, who are blackmailing the Kims. By now the suseok (stripped of its base and box) isn’t just a fancy collectible. Chekhov famously said that a gun that appears in the first act of a play must later be shot, and Parasite‘s suseok would make Chekhov proud. The sculptural rock returns as a weapon, as we watch the man hidden in the Parks’ bunker use it to smash Ki-woo’s head in, over and over.

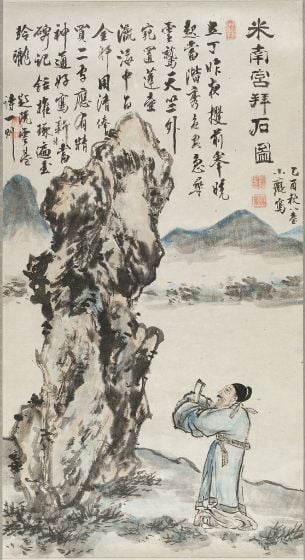

An 1885 Korean painting of the Chinese scholar Mi Fu (1051-1107) paying homage to a fantastic rock, by Hô Ryôn. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

How are suseok made?

Prized suseok are found in nature. Ideally, they’re never altered by human hands. “In China or Japan, in order to accentuate the dramatic effect, they put varnish types of materials or trim a little bit,” Pyun notes. “But for Korean rock collectors, the essence is you never touch it. As is, the nature is the beauty of the rock.”

Hardcore collectors, who often fish suseok out of river streams, look for rocks that are whole entities. “It’s not like they’re going to cut out a chunk from a cliff or a rock,” says Pyun. “It doesn’t work that way.”

Who owns them in real life? How fancy are they?

Suseok grace the homes of sophisticated Korean families, but they’re not the highest valued Korean art objects—painting and calligraphy come first. “In the hierarchy of collectors, people who only collect rocks are at the bottom 30 percent,” Pyun explains, noting that top-tier art collectors might have one or two suseok, but don’t make it the focal point of their collection.

This stratification matches the hierarchy in Parasite, with the basement-dwelling Kims and their suseok reflecting the lowest level of would-be collectors.

When did suseok become popular?

The golden age of suseok collecting was during the Joseun dynasty (1392–1897), but they regained popularity in the 1980s among a class of businessmen (like Parasite’s newly wealthy Mr. Park).

The Korean economy was burgeoning during that decade and produced fresh wealth among manufacturers of clothing, wigs, and sneakers. With their new resources, these businesspeople rejuvenated the suseok tradition. “Nouveau riche [suseok collectors] are usually businesspeople, who are self-made and come from not a great academic background, but somehow made a lot of money,” Pyun notes.

“Old money doesn’t collect rocks,” she adds. “It’s new people, who need to adapt to a new status but also want to exude this air of sophistication. It’s like an easy step towards sophistication.”

A suseok is the perfect gift for Parasite’s lowly Kims, who want a shortcut to the rarefied lifestyle of the filthy rich Parks. In the film’s bloody universe, though, this fabled rock isn’t a step towards sophistication; it’s an invitation to violence.

Check out this related article in the Guardian, "Built on rock: the geology at the heart of Oscars sensation Parasite" by Eve Willis, posted Feb 17, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment